British credit crisis of 1772–1773

The British credit crisis of 1772–1773, also known as the crisis of 1772, or the panic of 1772, was a peacetime financial crisis which originated in London and then spread to Scotland and the Dutch Republic. It has been described as the first modern banking crisis faced by the Bank of England. New colonies, as Adam Smith observed, had an insatiable demand for capital. Accompanying the more tangible evidence of wealth creation was a rapid expansion of credit and banking, leading to a rash of speculation and dubious financial innovation. In today's language, they bought shares on margin.

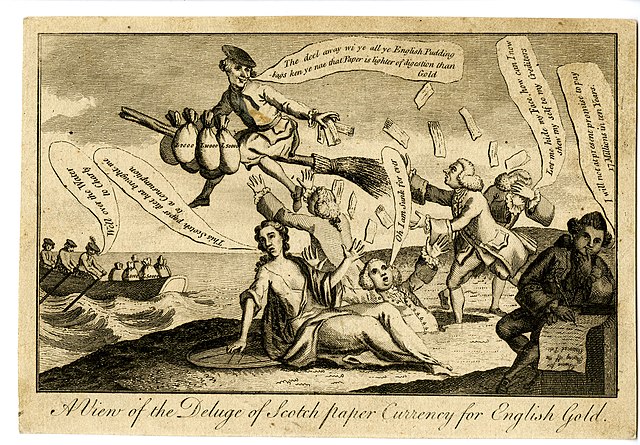

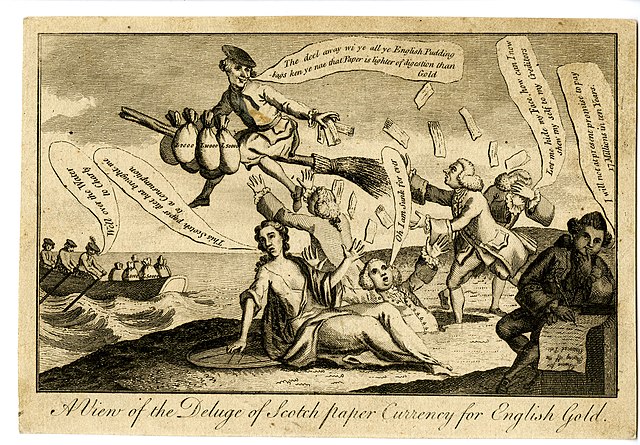

A view of the deluge of Scotch paper currency for English gold. A Scotsman in the air astride a broom is carrying off six large money-bags, three being inscribed "£2,000", "£10,000", and "£50,000". He scatters banknotes or bills; men on the ground, some sinking into a bog. exclaim in horror at his action. In the centre Britannia is seated, she says: "This Scotch paper diet has brought me to a consumption". In the foreground (r.) Lord North seated

Dividend Day at the Bank of England, 1770

Alexander Fordyce, a macaroni gambler with four dice.

Keizersgracht 444–448 was owned by Hope & Co

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with banking panics, and many recessions coincided with these panics. Other situations that are often called financial crises include stock market crashes and the bursting of other financial bubbles, currency crises, and sovereign defaults. Financial crises directly result in a loss of paper wealth but do not necessarily result in significant changes in the real economy.

Black Friday, 9 May 1873, Vienna Stock Exchange. The Panic of 1873 and Long Depression followed.

Declining consumer spending

The Roman denarius was debased over time.

Philip II of Spain defaulted four times on Spain's debt.