In the textual criticism of the New Testament, the Byzantine text-type is one of the main text types. It is the form found in the largest number of surviving manuscripts of the Greek New Testament. The New Testament text of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Patriarchal Text, as well as those utilized in the lectionaries, are based on this text-type. Similarly, the Aramaic Peshitta which often conforms to the Byzantine text is used as the standard version in the Syriac tradition, including the Syriac Orthodox Church and the Chaldean church. Whilst varying in at least 1,830 places, it also underlies the Textus Receptus Greek text used for most Reformation-era (Protestant) translations of the New Testament into vernacular languages. Modern translations mainly use eclectic editions that conform more often to the Alexandrian text-type, which is viewed as the most accurate text-type by most scholars, although some modern translations that use the Byzantine text-type have been created.

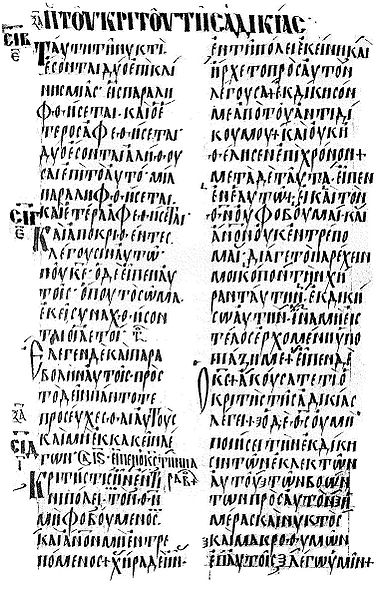

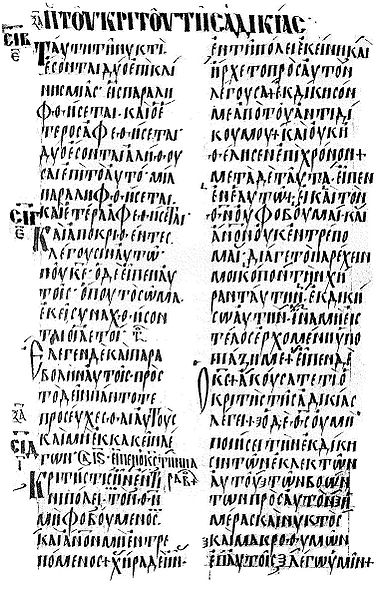

Codex Vaticanus 354 S (028), an uncial codex with a Byzantine text, assigned to the Family K1

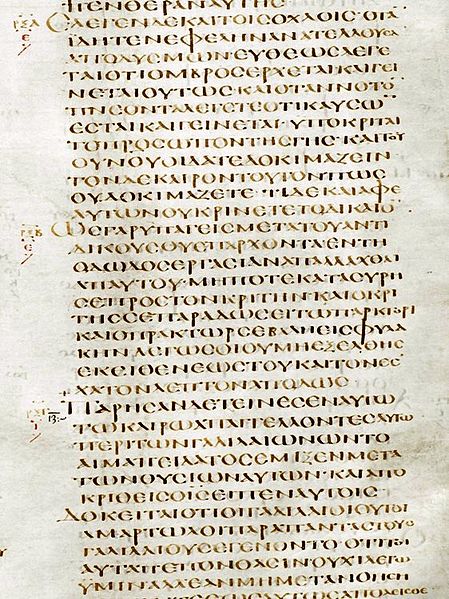

Codex Alexandrinus, the oldest Greek witness of the Byzantine text in the Gospels, close to the Family Π (Luke 12:54-13:4)

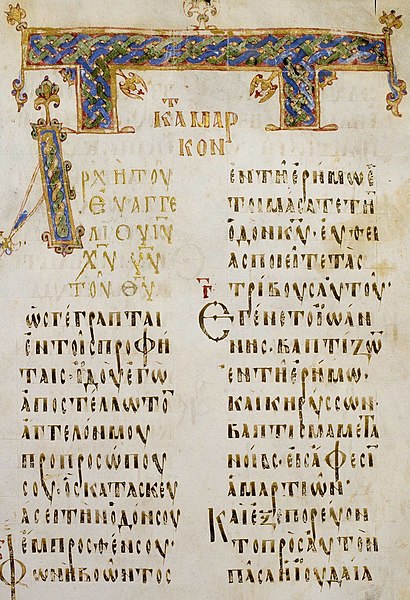

Evangelist portrait of Mark from Garima 2, likely the earlier of the two Garima Gospels

Codex Boreelianus, Byzantine manuscript, member of the Family E

Textual criticism of the New Testament

Textual criticism of the New Testament is the identification of textual variants, or different versions of the New Testament, whose goals include identification of transcription errors, analysis of versions, and attempts to reconstruct the original text. Its main focus is studying the textual variants in the New Testament.

A folio from Papyrus 46, one of the oldest extant New Testament manuscripts

Byzantine illuminated manuscript, 1020

Westcott and Hort's Introduction and Appendix (1882)