In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary, at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

View from the nave of the chancel of Condom Cathedral in France, with ambulatories and two altars, the modern one in the choir

St Peter's, Lilley, Hertfordshire a medium-sized English church showing the nave, chancel arch, and a chancel with choir and sanctuary

Iron entry gates to the chancel at the Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd (Rosemont, Pennsylvania), USA, designed by master blacksmith Samuel Yellin

Church architecture refers to the architecture of Christian buildings, such as churches, chapels, convents, seminaries, etc. It has evolved over the two thousand years of the Christian religion, partly by innovation and partly by borrowing other architectural styles as well as responding to changing beliefs, practices and local traditions. From the Early Christianity to the present, the most significant objects of transformation for Christian architecture and design were the great churches of Byzantium, the Romanesque abbey churches, Gothic cathedrals and Renaissance basilicas with its emphasis on harmony. These large, often ornate and architecturally prestigious buildings were dominant features of the towns and countryside in which they stood. However, far more numerous were the parish churches in Christendom, the focus of Christian devotion in every town and village. While a few are counted as sublime works of architecture to equal the great cathedrals and churches, the majority developed along simpler lines, showing great regional diversity and often demonstrating local vernacular technology and decoration.

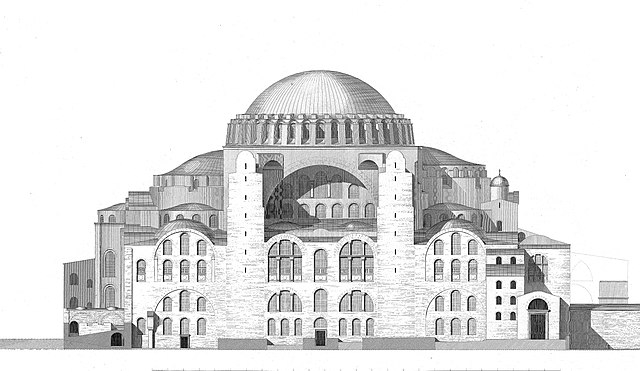

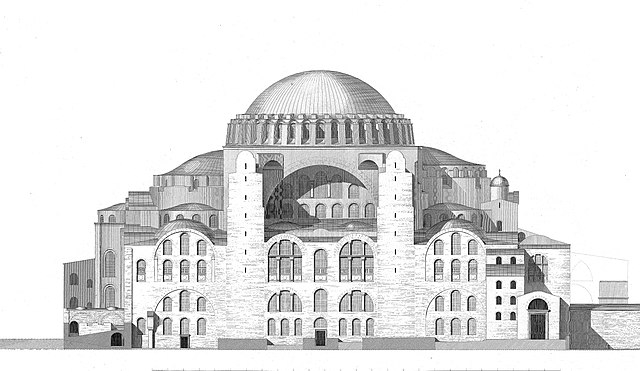

Image: Saint Sophia, Constantinopolis

Image: Basilique Saint Pierre Vatican (VA) 2021 08 25 4

Image: St Paul's Cathedral Nave, London, UK Diliff

The 800-year-old Ursuskerk of Termunten in the north of the Netherlands