Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae

The Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae, also referred to as the Bonn Corpus, is a monumental fifty-volume series of primary sources for the study of Byzantine history, published in the German city of Bonn between 1828 and 1897. Each volume contains a critical edition of a Byzantine Greek historical text, accompanied by a parallel Latin translation. The project, conceived by the historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr, sought to revise and expand the original twenty-four volume Corpus Byzantinae Historiae, published in Paris between 1648 and 1711 under the initial direction of the Jesuit scholar Philippe Labbe. The series was first based at the University of Bonn; after Niebuhr's death in 1831, however, oversight of the project passed to his collaborator Immanuel Bekker at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin.

Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae

Text (the History of Nikephoros Gregoras) from the CSHB

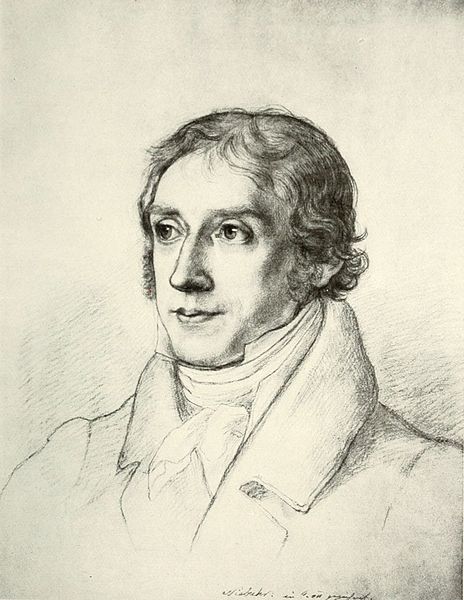

Barthold Georg Niebuhr was a Danish–German statesman, banker, and historian who became Germany's leading historian of Ancient Rome and a founding father of modern scholarly historiography. By 1810 Niebuhr was inspiring German patriotism in students at the University of Berlin by his analysis of Roman economy and government. Niebuhr was a leader of the Romantic era and symbol of German national spirit that emerged after the defeat at Jena. But he was also deeply rooted in the classical spirit of the Age of Enlightenment in his intellectual presuppositions, his use of philologic analysis, and his emphasis on both general and particular phenomena in history.

Barthold Georg Niebuhr (drawing by Louise Seidler)