Diamagnetism is the property of materials that are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials are attracted by a magnetic field. Diamagnetism is a quantum mechanical effect that occurs in all materials; when it is the only contribution to the magnetism, the material is called diamagnetic. In paramagnetic and ferromagnetic substances, the weak diamagnetic force is overcome by the attractive force of magnetic dipoles in the material. The magnetic permeability of diamagnetic materials is less than the permeability of vacuum, μ0. In most materials, diamagnetism is a weak effect which can be detected only by sensitive laboratory instruments, but a superconductor acts as a strong diamagnet because it entirely expels any magnetic field from its interior.

![Pyrolytic carbon has one of the largest diamagnetic constants[clarification needed] of any room temperature material. Here a pyrolytic carbon sheet is](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/Diamagnetic_graphite_levitation.jpg/471px-Diamagnetic_graphite_levitation.jpg)

Pyrolytic carbon has one of the largest diamagnetic constants[clarification needed] of any room temperature material. Here a pyrolytic carbon sheet is levitated by its repulsion from the strong magnetic field of neodymium magnets

A live frog levitates inside a 32 mm (1.26 in) diameter vertical bore of a Bitter solenoid in a magnetic field of about 16 teslas at the Nijmegen High Field Magnet Laboratory.

A magnetic field is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the magnetic field. A permanent magnet's magnetic field pulls on ferromagnetic materials such as iron, and attracts or repels other magnets. In addition, a nonuniform magnetic field exerts minuscule forces on "nonmagnetic" materials by three other magnetic effects: paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and antiferromagnetism, although these forces are usually so small they can only be detected by laboratory equipment. Magnetic fields surround magnetized materials, electric currents, and electric fields varying in time. Since both strength and direction of a magnetic field may vary with location, it is described mathematically by a function assigning a vector to each point of space, called a vector field.

A solenoid (electromagnet), a coil of wire with an electric current through it

One of the first drawings of a magnetic field, by René Descartes, 1644, showing the Earth attracting lodestones. It illustrated his theory that magnetism was caused by the circulation of tiny helical particles, "threaded parts", through threaded pores in magnets.

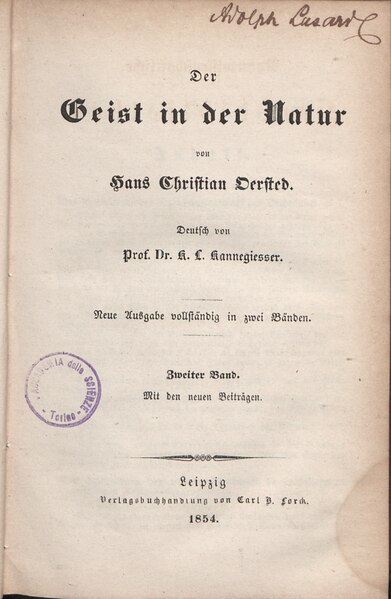

Hans Christian Ørsted, Der Geist in der Natur, 1854

![Pyrolytic carbon has one of the largest diamagnetic constants[clarification needed] of any room temperature material. Here a pyrolytic carbon sheet is](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/Diamagnetic_graphite_levitation.jpg/471px-Diamagnetic_graphite_levitation.jpg)