A draft horse (US) or draught horse (UK), also known as dray horse, carthorse, work horse or heavy horse, is a large horse bred to be a working animal hauling freight and doing heavy agricultural tasks such as plowing. There are a number of breeds, with varying characteristics, but all share common traits of strength, patience, and a docile temperament.

A draft horse is generally a large, heavy horse suitable for farm labor, like this Shire horse.

Comparison of a typical-sized carriage horse (top) to a heavy draft horse (bottom)

Two horses hitched to a plow.

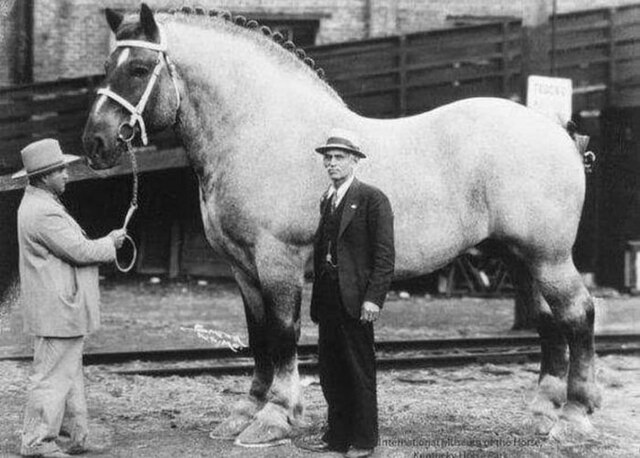

Brooklyn Supreme (1928-1948) a Belgian draft horse, 198 cm (19.2 hands) high and weighed 1,451 kg (3,200 lb)

The horse is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of Equus ferus. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million years from a small multi-toed creature, close to Eohippus, into the large, single-toed animal of today. Humans began domesticating horses around 4000 BCE, and their domestication is believed to have been widespread by 3000 BCE. Horses in the subspecies caballus are domesticated, although some domesticated populations live in the wild as feral horses. These feral populations are not true wild horses, which are horses that never have been domesticated and historically linked to the megafauna category of species. There is an extensive, specialized vocabulary used to describe equine-related concepts, covering everything from anatomy to life stages, size, colors, markings, breeds, locomotion, and behavior.

Horse

Points of a horse

Size varies greatly among horse breeds, as with this full-sized horse and small pony.

Bay (left) and chestnut (sometimes called "sorrel") are two of the most common coat colors, seen in almost all breeds.