Environmental studies is a multidisciplinary academic field which systematically studies human interaction with the environment. Environmental studies connects principles from the physical sciences, commerce/economics, the humanities, and social sciences to address complex contemporary environmental issues. It is a broad field of study that includes the natural environment, the built environment, and the relationship between them. The field encompasses study in basic principles of ecology and environmental science, as well as associated subjects such as ethics, geography, anthropology, public policy, education, political science, urban planning, law, economics, philosophy, sociology and social justice, planning, pollution control, and natural resource management. There are many Environmental Studies degree programs, including a Master's degree and a Bachelor's degree. Environmental Studies degree programs provide a wide range of skills and analytical tools needed to face the environmental issues of our world head on. Students in Environmental Studies gain the intellectual and methodological tools to understand and address the crucial environmental issues of our time and the impact of individuals, society, and the planet. Environmental education's main goal is to instill in all members of society a pro-environmental thinking and attitude. This will help to create environmental ethics and raise people's awareness of the importance of environmental protection and biodiversity.

The Porter School of Environmental Studies Building – Tel Aviv University

Environmental science is an interdisciplinary academic field that integrates physics, biology, and geography to the study of the environment, and the solution of environmental problems. Environmental science emerged from the fields of natural history and medicine during the Enlightenment. Today it provides an integrated, quantitative, and interdisciplinary approach to the study of environmental systems.

Rachel Carson published her groundbreaking novel, Silent Spring, in 1962, bringing the study of environmental science to the forefront of society.

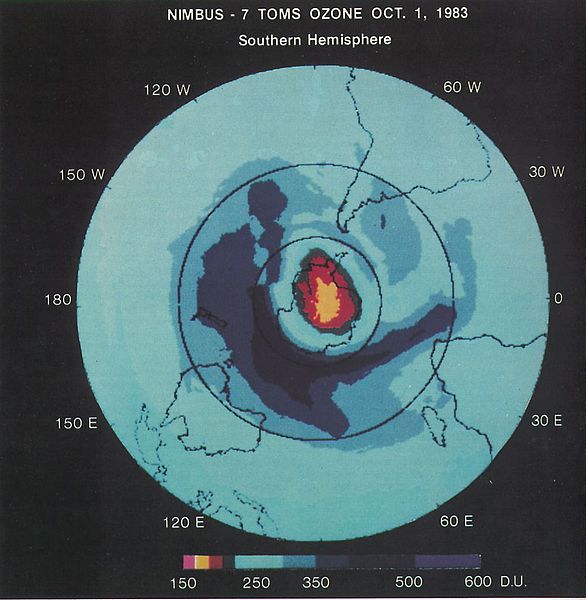

A team of British researchers found a hole in the ozone layer forming over Antarctica, the discovery of which would later influence the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

The Paris Agreement (formerly the Kyoto Protocol) is adopted in 2016. Nearly every country in the United Nations has signed the treaty, which aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Blue Marble composite images generated by NASA in 2001 (left) and 2002 (right)