Geography of South Africa

South Africa occupies the southern tip of Africa, its coastline stretching more than 2,850 kilometres from the desert border with Namibia on the Atlantic (western) coast southwards around the tip of Africa and then northeast to the border with Mozambique on the Indian (eastern) coast. The low-lying coastal zone is narrow for much of that distance, soon giving way to a mountainous escarpment that separates the coast from the high inland plateau. In some places, notably the province of KwaZulu-Natal in the east, a greater distance separates the coast from the escarpment. Although much of the country is classified as semi-arid, it has considerable variation in climate as well as topography. The total land area is 1,220,813 km2 (471,359 sq mi). It has the 23rd largest Exclusive Economic Zone of 1,535,538 km2 (592,875 sq mi).

The Southern African Central Plateau edged by the Great Escarpment.

Panorama of the Giant's Castle region of the Drakensberg, the highest section of the Great Escarpment. Here the Escarpment is capped by a 1,400 m layer of erosion-resistant lava, which once covered most of Southern Africa 182 million years ago. Only a small remnant of this lava layer remains on the plateau, covering only part of Lesotho, and accounting for the Great Escarpment's great height on the Lesotho/KwaZulu-Natal border.

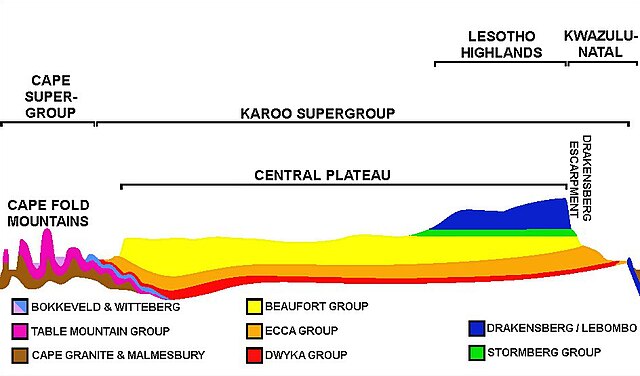

An approximate SW-NE cross section through South Africa with the Cape Peninsula (with Table Mountain) on left, and north-eastern KwaZulu-Natal on the right. Diagrammatic and only roughly to scale. It shows the major geological structures (coloured layers) that dominate the southern and eastern parts of the country, as well as the relationship between the Central Plateau, the Cape Fold Mountains, and the Drakensberg escarpment.

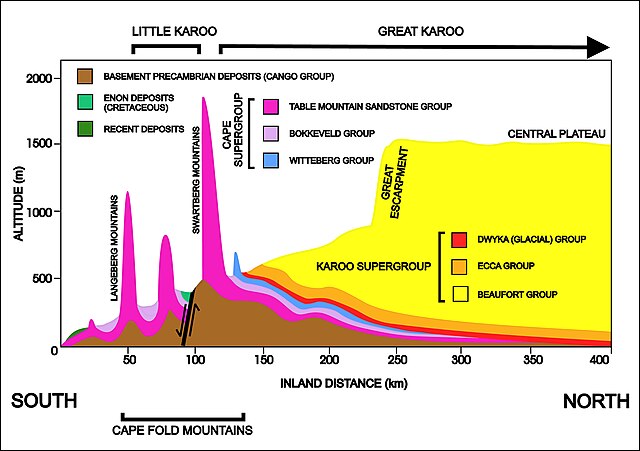

A diagrammatic 400 km north–south cross-section through the southern portion of the country near Calitzdorp in the Little Karoo (approximately 21° 30' E), showing the relationship between the Cape Fold Mountains (and their geological structure) and the geology of the Little and Great Karoo, as well as the position of the Great Escarpment. The colour code for the geological layers is the same as those used in the diagram on the left. The heavy black line flanked by opposing arrows is the fault that runs for nearly 300 km along the southern edge of the

The Karoo Supergroup is the most widespread stratigraphic unit in Africa south of the Kalahari Desert. The supergroup consists of a sequence of units, mostly of nonmarine origin, deposited between the Late Carboniferous and Early Jurassic, a period of about 120 million years.

An approximate SW-NE geological cross section through South Africa, with the Cape Peninsula (with Table Mountain) on left, and north-eastern KwaZulu-Natal on the right. Diagrammatic and not to scale. The color code of the Karoo Supergroup is the same as in the illustration above.

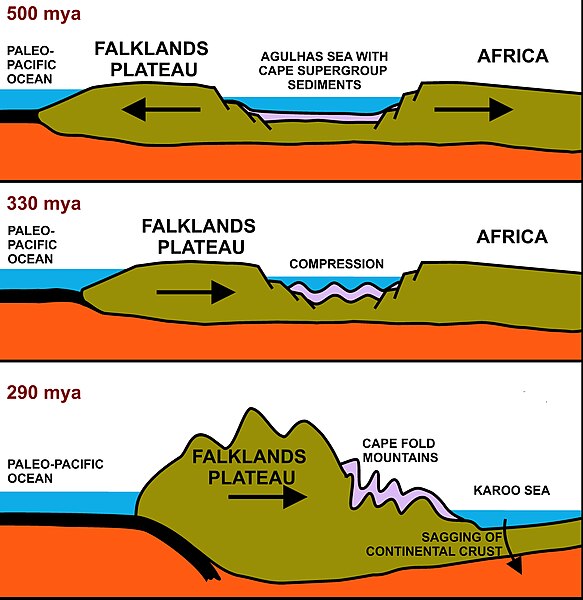

A north-south cross-section through the Agulhas Sea (see above). The brown structures are continental plates, the thick black layer on the left is paleo-Pacific Oceanic plate, red indicates the upper mantle, and blue indicates flooded areas or ocean. The top illustration depicts the geology about 510 million years ago, with the sediments which would eventually form the Cape Supergroup settling in the Agulhas Sea. The middle illustration depicts the Falkland Plateau drifting northwards once again to close the Agulhas Sea, causing the Cape Supergroup to be rucked into a series of folds, running predominantly east–west. The lowest illustration shows how subduction of the paleo-Pacific Oceanic plate under the Falkland Plateau, during the Early Permian period, raised a massive range of mountains. These eventually eroded into the Karoo Sea, forming, especially, the

Turbidites are deposited in deep water at the bottom of the edges of continental shelves or similar structures in deep lakes, such as the south-western Karoo Sea about 300 million years ago. They are the result of underwater avalanches of mud and sand cascading down the steep slope of the edge of the shelf. When the avalanche settles in the deep water trough, the sand and other coarse material settles first, then the mud and eventually the finest particles. Organic matter that came down with the avalanche ends up in the turbidite in an anoxic (oxygen free) environment where it is converted to

An Ecca mountain in the Tanqua Karoo, with multiple turbidite fans, indicating that the south-western portion of Karoo Sea was very deep, with steep slopes leading up to the shore line. The underwater avalanches were probably triggered by frequent earthquakes as the Cape Fold Mountains were being formed towards the south. The Ecca Turbidite deposits should not be confused with the dolerite sills found further inland (illustrated and described lower down, on the right, in the article) . The turbidites can be recognized at close quarters by the fact that the lowermost portion of each layer tends to be made up of sandstone which gradually grades into fine siltstone at the top of the layer.