Industrial melanism is an evolutionary effect prominent in several arthropods, where dark pigmentation (melanism) has evolved in an environment affected by industrial pollution, including sulphur dioxide gas and dark soot deposits. Sulphur dioxide kills lichens, leaving tree bark bare where in clean areas it is boldly patterned, while soot darkens bark and other surfaces. Darker pigmented individuals have a higher fitness in those areas as their camouflage matches the polluted background better; they are thus favoured by natural selection. This change, extensively studied by Bernard Kettlewell (1907–1979), is a popular teaching example in Darwinian evolution, providing evidence for natural selection. Kettlewell's results have been challenged by zoologists, creationists and the journalist Judith Hooper, but later researchers have upheld Kettlewell's findings.

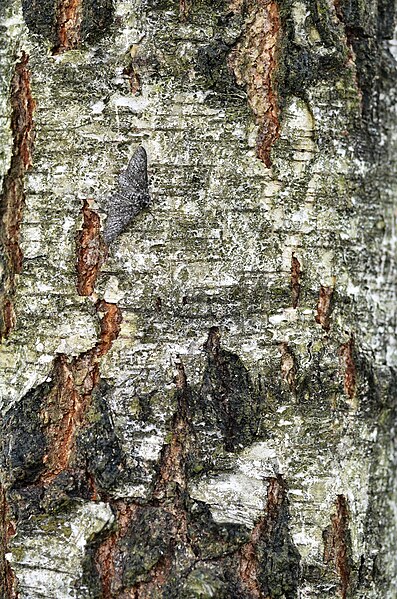

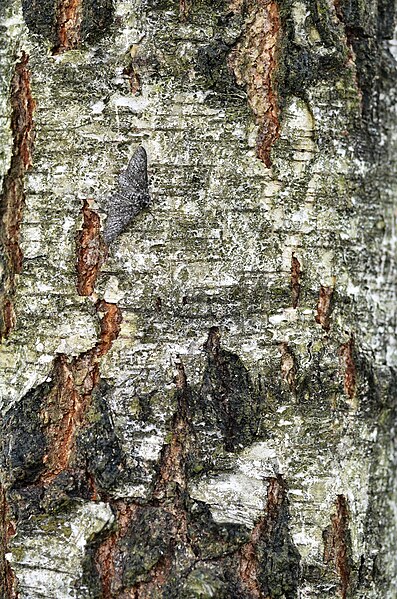

Intermediate insularia form (between pale typica and dark carbonaria in tone) of peppered moth on a lichen-covered birch tree: Bernard Kettlewell counted the frequencies of all three forms.

Tree bark covered in shrubby and leafy lichens forms a patterned background against which non-melanic disruptively patterned moth camouflage is effective.

Image: Odontopera bidentata, Scalloped Hazel, Trawscoed, North Wales, June 2016 Flickr janetgraham 84

Image: Odontopera bidentata (7275071212)

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the battledress of a modern soldier, and the leaf-mimic katydid's wings. A third approach, motion dazzle, confuses the observer with a conspicuous pattern, making the object visible but momentarily harder to locate, as well as making general aiming easier. The majority of camouflage methods aim for crypsis, often through a general resemblance to the background, high contrast disruptive coloration, eliminating shadow, and countershading. In the open ocean, where there is no background, the principal methods of camouflage are transparency, silvering, and countershading, while the ability to produce light is among other things used for counter-illumination on the undersides of cephalopods such as squid. Some animals, such as chameleons and octopuses, are capable of actively changing their skin pattern and colours, whether for camouflage or for signalling. It is possible that some plants use camouflage to evade being eaten by herbivores.

The peacock flounder can change its pattern and colours to match its environment.

A soldier applying camouflage face paint; both helmet and jacket are disruptively patterned.

Octopuses like this Octopus cyanea can change colour (and shape) for camouflage

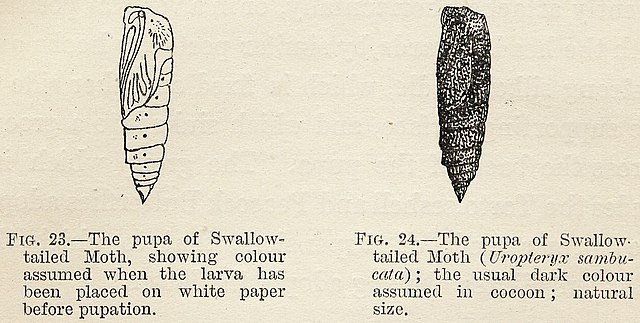

Experiment by Poulton, 1890: swallowtailed moth pupae with camouflage they acquired as larvae