A kyaung is a monastery (vihara), comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Buddhist monks. Burmese kyaungs are sometimes also occupied by novice monks (samanera), lay attendants (kappiya), nuns (thilashin), and white-robed acolytes.

An urban kyaung on Anawrahta Road in Yangon

A traditional wooden monastery.

A 19th-century watercolor depicting a kyaung with masonry balustrades.

A 19th-century watercolor depicting a more prominent kyaung as indicated by the presence of a multi-tiered pyatthat roof.

Burmese is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken in Myanmar, where it is the official language, lingua franca, and the native language of the Bamar, the country's principal ethnic group. Burmese is also spoken by the indigenous tribes in Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh, and in Tripura state in India. The Constitution of Myanmar officially refers to it as the Myanmar language in English, though most English speakers continue to refer to the language as Burmese, after Burma—a name with co-official status that had historically been predominantly used for the country. Burmese is the most widely-spoken language in the country, where it serves as the lingua franca. In 2007, it was spoken as a first language by 33 million. Burmese is spoken as a second language by another 10 million people, including ethnic minorities in Myanmar like the Mon and also by those in neighboring countries. In 2022, the Burmese-speaking population was 38.8 million.

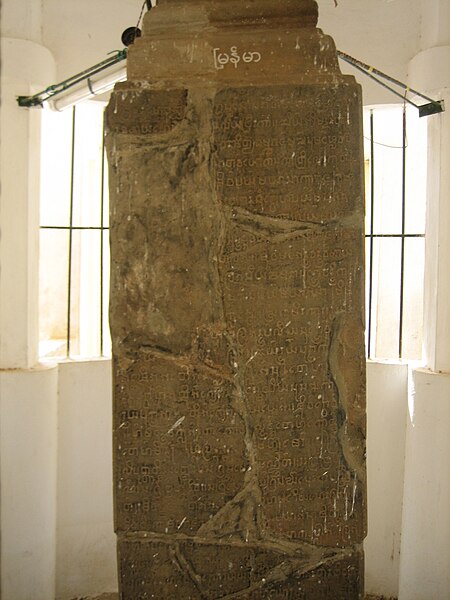

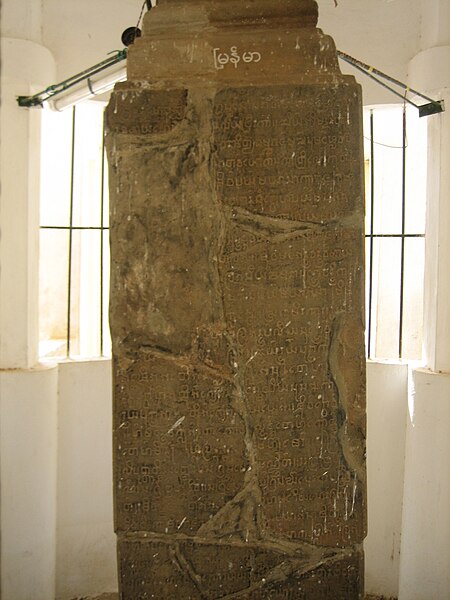

The Myazedi inscription, dated to AD 1113, is the oldest surviving stone inscription of the Burmese language.

Sampling of various Burmese script styles