A lampshade is a fixture that envelops the lightbulb on a lamp to diffuse the light it emits. Lampshades can be made out of a large variety of materials like paper, glass, fabric, stone, or any material that let light in. Oftentimes conical or cylindrical in shape, lampshades can be found on floor, desk, tabletop, or suspended lamps. The term can also apply to the glass hung around many designs of ceiling lamp. Beyond its practical purpose, significant emphasis is also usually given to decorative and aesthetic features. A lamp shade also serves to "shade" human eyes from the direct glare of the light bulbs used to illuminate the lamp. Some lamp shades are also lined with a hard-backed opaque lining, often white or gold, to reflect as much light as possible through the top and bottom of the shade while blocking light from emitting through the walls of the shade itself. In other cases, the shade material is deliberately decorative so that upon illumination it may emphasize a display of color and light emitting through the shade surface itself.

Two modern electric lamps with lampshades.

An Argand oil lamp in use with a glass shade, 1822

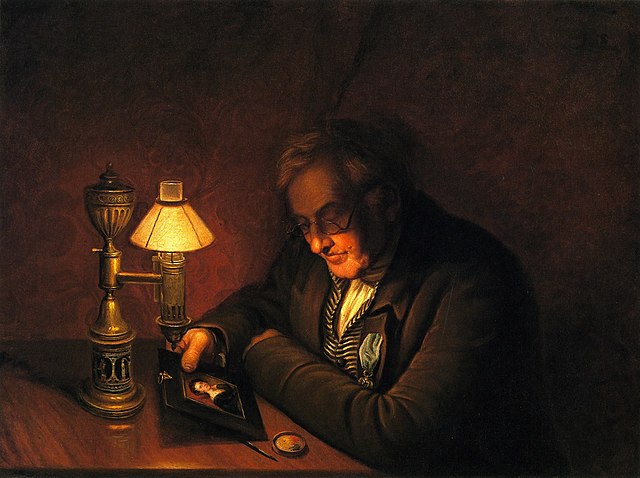

Adjustable tole (painted tin) candleshade in a Russian portrait, c. 1830s

A light fixture, light fitting, or luminaire is an electrical lighting device containing one or more light sources, such as lamps, and all the accessory components required for its operation to provide illumination to the environment. All light fixtures have a fixture body and one or more lamps. The lamps may be in sockets for easy replacement—or, in the case of some LED fixtures, hard-wired in place.

Lamp and lampshade made of Tiffany glass; c. 1890–1900; Budapest Museum of Applied Arts (Budapest, Hungary)

Lamp; 1902–1918; lead and glass; 67.9 x 52.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

"Daffodil" lamp; 1904–1924; leaded opalescent glass and gilt bronze; height: 67.9 cm, diameter of shape: 51.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Chandeliers in the Bibliothèque Mazarine (Paris)