Objective idealism is a philosophical theory that affirms the ideal and spiritual nature of the world and conceives of the idea of which the world is made as the objective and rational form in reality rather than as subjective content of the mind or mental representation. Objective idealism thus differs both from materialism, which holds that the external world is independent of cognizing minds and that mental processes and ideas are by-products of physical events, and from subjective idealism, which conceives of reality as totally dependent on the consciousness of the subject and therefore relative to the subject itself.

Charles Sanders Peirce is among the most prominent modern proponents of objective idealism.

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical idealism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is entirely a mental construct; or that ideas are the highest type of reality or have the greatest claim to being considered "real". Because there are different types of idealism, it is difficult to define the term uniformly.

The Upanishadic sage Yājñavalkya (c. possibly 8th century BCE) is one of the earliest exponents of idealism, and is a major figure in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad.

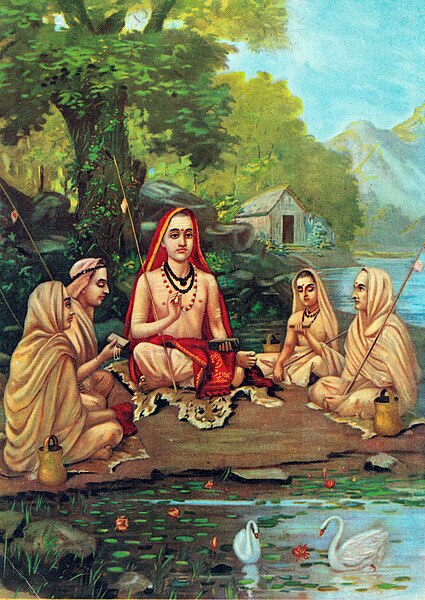

Śaṅkara, by Raja Ravi Varma

Statue of Vasubandhu (jp. Seshin), Kōfuku-ji, Nara, Japan

Wang Yangming, a leading Neo-Confucian scholar during the Ming and a founder of the "school of mind".