The ancient legend of Orpheus and Eurydice concerns the fateful love of Orpheus of Thrace for the beautiful Eurydice. Orpheus was the son of Oeagrus and the muse Calliope. It may be a late addition to the Orpheus myths, as the latter cult-title suggests those attached to Persephone. The subject is among the most frequently retold of all Greek myths, being featured in numerous works of literature, operas, ballets, paintings, plays, musicals, and more recently, films and video games.

Egyptian tapestry roundel with Orpheus and Apollo, 5th–6th century CE

Orpheus and Eurydice in Palais Garnier, Paris. Their names are in Greek, ΟΡΦΕΥΣ (Orpheus) and ΕΥΡΥΔΙΚΗ (Eurydice).

Orpheus Mourning the Death of Eurydice, 1814 painting by Ary Scheffer.

Orpheus glances back at Eurydice, 1806 oil painting by Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein Stub.

The Georgics is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example of peaceful rural poetry, it is a work characterized by tensions in both theme and purpose.

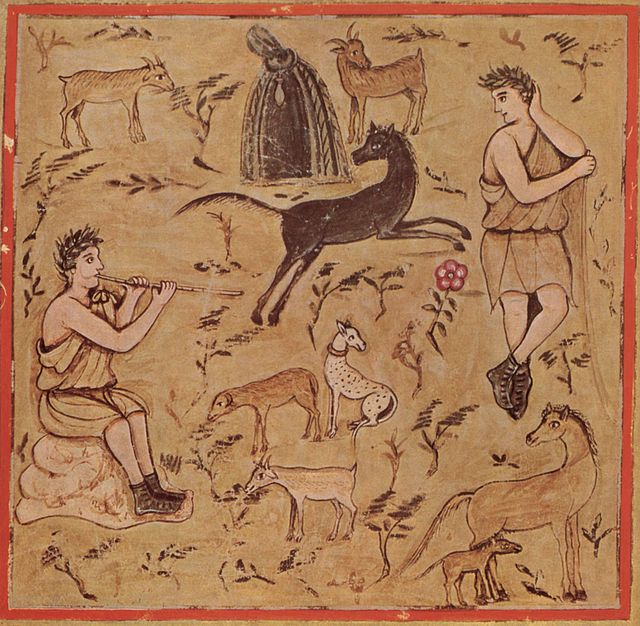

Georgics Book III, shepherd with flocks, Roman Virgil.

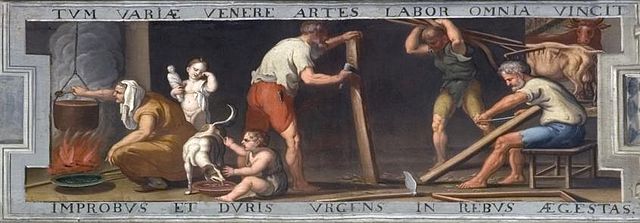

One of four Polish frieze paintings in the King's palace at Wilanów illustrating Georgics Book I, 1683

Fourth book of Virgil’s Georgics in ms. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vaticanus Palatinus lat. 1632, fol. 51v.

Cristoforo Majorana – Leaf from Eclogues, Georgics and Aeneid – Walters W40016V – Open Reverse