Paul of Aegina or Paulus Aegineta was a 7th-century Byzantine Greek physician best known for writing the medical encyclopedia Medical Compendium in Seven Books. He is considered the “Father of Early Medical Writing”. For many years in the Byzantine Empire, his works contained the sum of all Western medical knowledge and was unrivaled in its accuracy and completeness.

Historiated initial from a 16th-century edition.

Surgery is the branch of medicine that deals with the physical manipulation of a bodily structure to diagnose, prevent, or cure an ailment. Ambroise Paré, a 16th-century French surgeon, stated that to perform surgery is, "To eliminate that which is superfluous, restore that which has been dislocated, separate that which has been united, join that which has been divided and repair the defects of nature."

The Extraction of the Stone of Madness (The Cure of Folly) by Hieronymous Bosch

Pictures of surgery tools at Kom Ombo, Egypt

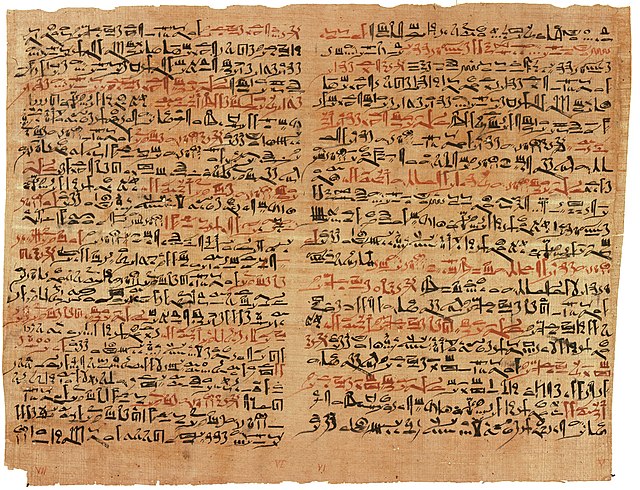

Plates vi and vii of the Edwin Smith Papyrus (around the 17th century BC), among the earliest medical texts

A statue of Sushruta (800 BCE), author of Sushruta Samhita and the founding father of surgery, at Royal Australasian College of Surgeons in Melbourne, Australia