Post-glacial rebound is the rise of land masses after the removal of the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, which had caused isostatic depression. Post-glacial rebound and isostatic depression are phases of glacial isostasy, the deformation of the Earth's crust in response to changes in ice mass distribution. The direct raising effects of post-glacial rebound are readily apparent in parts of Northern Eurasia, Northern America, Patagonia, and Antarctica. However, through the processes of ocean siphoning and continental levering, the effects of post-glacial rebound on sea level are felt globally far from the locations of current and former ice sheets.

This layered beach at Bathurst Inlet, Nunavut is an example of post-glacial rebound after the last Ice Age. Little to no tide helped to form its layer-cake look. Isostatic rebound is still underway here.

Changes in the elevation of Lake Superior due to glaciation and post-glacial rebound

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi). The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice sheets are bigger than ice shelves or alpine glaciers. Masses of ice covering less than 50,000 km2 are termed an ice cap. An ice cap will typically feed a series of glaciers around its periphery.

One of Earth's two ice sheets: The Antarctic ice sheet covers about 98% of the Antarctic continent and is the largest single mass of ice on Earth. It has an average thickness of over 2 kilometers.

Glacial flow rate in the Antarctic ice sheet.

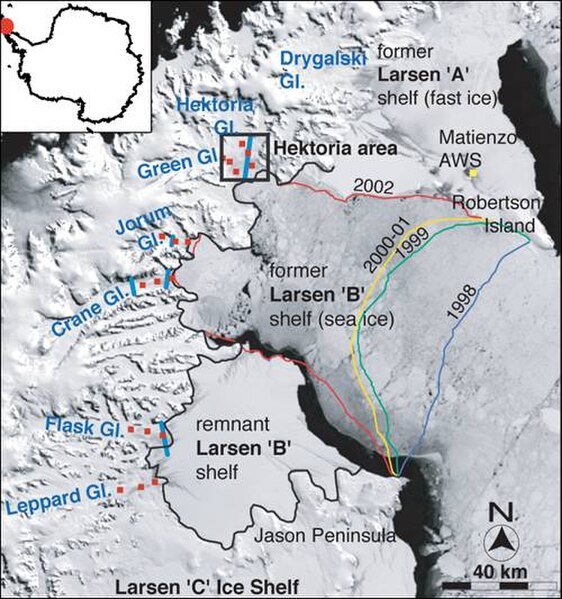

The collapse of the Larsen B ice shelf had profound effects on the velocities of its feeder glaciers.

Accelerated ice flows after the break-up of an ice shelf