Slave markets and slave jails in the United States

Slave markets and slave jails in the United States were places used for the slave trade in the United States from the founding in 1776 until the total abolition of slavery in 1865. Slave pens, also known as slave jails, were used to temporarily hold enslaved people until they were sold, or to hold fugitive slaves, and sometimes even to "board" slaves while traveling. Slave markets were any place where sellers and buyers gathered to make deals. Some of these buildings had dedicated slave jails, others were negro marts to showcase the slaves offered for sale, and still others were general auction or market houses where a wide variety of business was conducted, of which "negro trading" was just one part.

Price, Birch & Co., "dealers in slaves" Alexandria, Virginia, photographed c. 1862

In addition to private jails, enslaved people were often held in public jails, such as a 40-year-old fugitive man named Monday who fought "like the Devil when arrested" and who was held in the jail of Walker County, Alabama (The Democrat, Huntsville, July 7, 1847)

Claimed to be Nathan Bedford Forrest's slave pen ("The Old Negro Mart" Memphis Commercial Appeal, January 27, 1907)

"Sale of Estates, Pictures and Slaves in the Rotunda at New Orleans" by William Henry Brooke from The Slave States of America (1842) by James Silk Buckingham depicts a slave sale at the St. Louis Hotel, sometimes called the French Exchange

Slave trade in the United States

The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

When interviewed in 1913 by Myra Williams Jarrell for the Topeka Star, Emily Ford and Mary Shawn of Burlingame, Kansas, recalled an instance of family separation in American slavery due to the slave trade

Partial manifest of a coastwise slave shipment made from Baltimore to New Orleans, by Hope H. Slatter, on the ship Scotia, September 1843

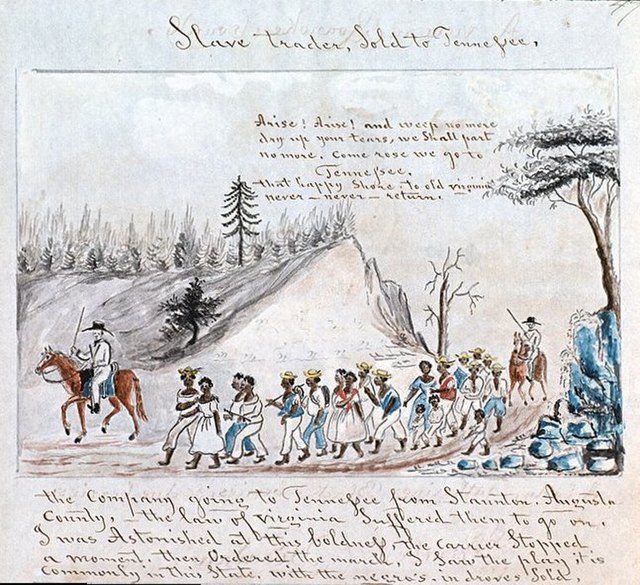

"Slave Trader, Sold to Tennessee" by an unknown artist

1844 newspaper icon depicting white man with suit and cane, and shackled enslaved black person