Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art is a 1993 non-fiction work of comics by American cartoonist Scott McCloud. It explores formal aspects of comics, the historical development of the medium, its fundamental vocabulary, and various ways in which these elements have been used. It expounds theoretical ideas about comics as an art form and medium of communication, and is itself written in comic book form.

Cover of the original Tundra Publishing edition of Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art.

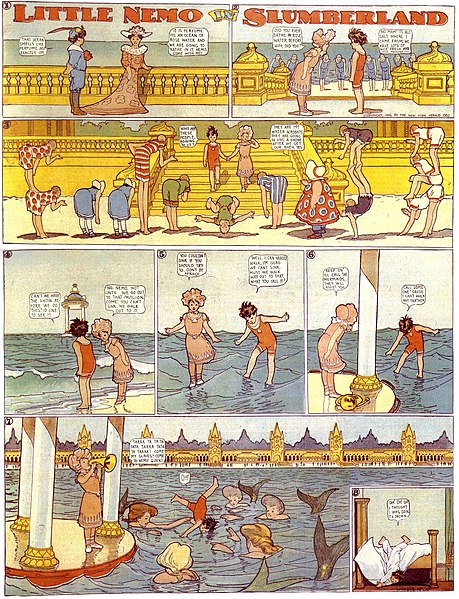

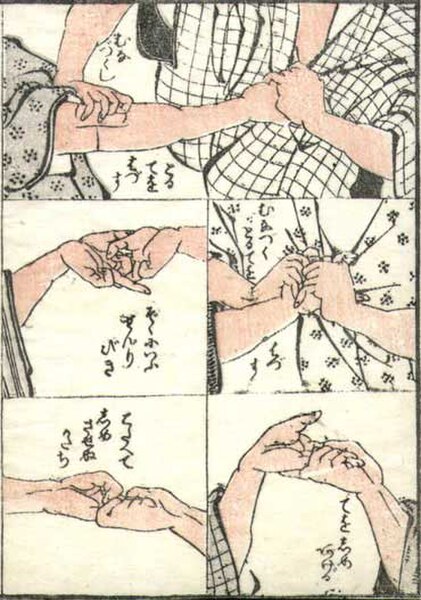

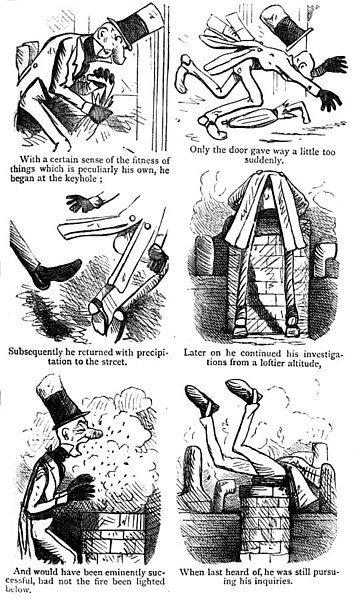

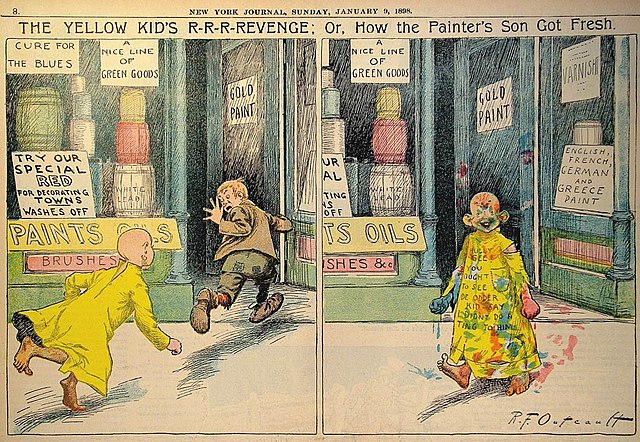

Comics are a medium used to express ideas with images, often combined with text or other visual information. It typically takes the form of a sequence of panels of images. Textual devices such as speech balloons, captions, and onomatopoeia can indicate dialogue, narration, sound effects, or other information. There is no consensus among theorists and historians on a definition of comics; some emphasize the combination of images and text, some sequentiality or other image relations, and others historical aspects such as mass reproduction or the use of recurring characters. Cartooning and other forms of illustration are the most common image-making means in comics; Photo comics is a form that uses photographic images. Common forms include comic strips, editorial and gag cartoons, and comic books. Since the late 20th century, bound volumes such as graphic novels, comic albums, and tankōbon have become increasingly common, along with webcomics as well as scientific/medical comics.

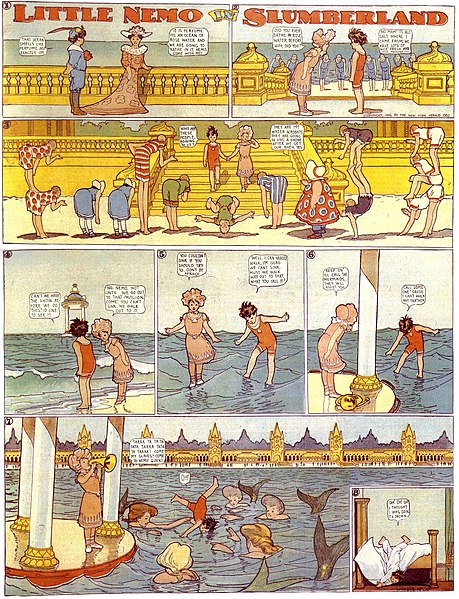

Little Nemo, August 19, 1906 strip

Manga Hokusai, early 19th century

Ally Sloper in Some of the Mysteries of Loan and Discount Charles Henry Ross, 1867

The Yellow Kid R. F. Outcault, 1898