Valentinian dynasty

Videos

Page

The Valentinian dynasty was a ruling house of five generations of dynasts, including five Roman emperors during Late Antiquity, lasting nearly a hundred years from the mid fourth to the mid fifth century. They succeeded the Constantinian dynasty and reigned over the Roman Empire from 364 to 392 and from 425 to 455, with an interregnum (392–423), during which the Theodosian dynasty ruled and eventually succeeded them. The Theodosians, who intermarried into the Valentinian house, ruled concurrently in the east after 379.

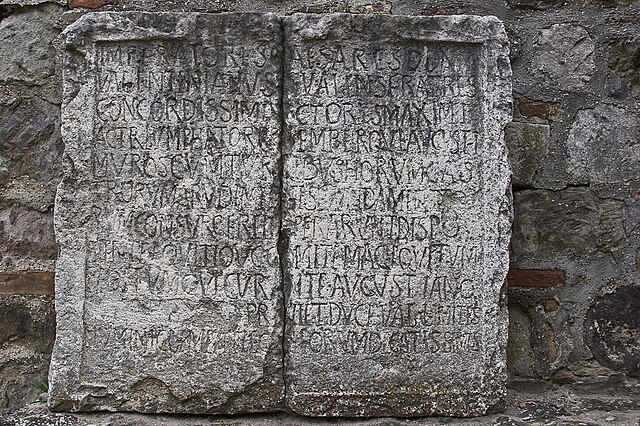

Inscription to Valentinian I and Valens from Esztergom on the Danube

Solidus of Valentinian I showing Valentinian and Gratian on the reverse, marked: victores augusti ("the Victors Augusti"). A palm bough is between them and Victory crowns each with a wreath

Death of Valentinianus Galates from the 9th-century Paris Gregory (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Detail of drawing of obverse of medal of Valens showing the three reigning emperors: Valens (C), Gratian (R), and Valentinian II (L) and marked: pietas d·d·d·n·n·n· augustorum

Constantinian dynasty

Videos

Page

The Constantinian dynasty is an informal name for the ruling family of the Roman Empire from Constantius Chlorus to the death of Julian in 363. It is named after its most famous member, Constantine the Great, who became the sole ruler of the empire in 324. The dynasty is also called Neo-Flavian because every Constantinian emperor bore the name Flavius, similarly to the rulers of the first Flavian dynasty in the 1st century.

Constantine I with his two eldest sons by Fausta, Constantine II and Constantius II

Silver coin of Constans, showing Constans, Constantine II and Constantius II