Imagery intelligence (IMINT), pronounced as either as Im-Int or I-Mint, is an intelligence gathering discipline wherein imagery is analyzed to identify information of intelligence value. Imagery used for defense intelligence purposes is generally collected via satellite imagery or aerial photography.

Sidney Cotton's Lockheed 12A, in which he made a high-speed reconnaissance flight in 1940.

Aerial photograph of the missile Test Stand VII at Peenemünde.

Soviet truck convoy deploying missiles near San Cristobal, Cuba, on Oct. 14, 1962 (taken by a U-2)

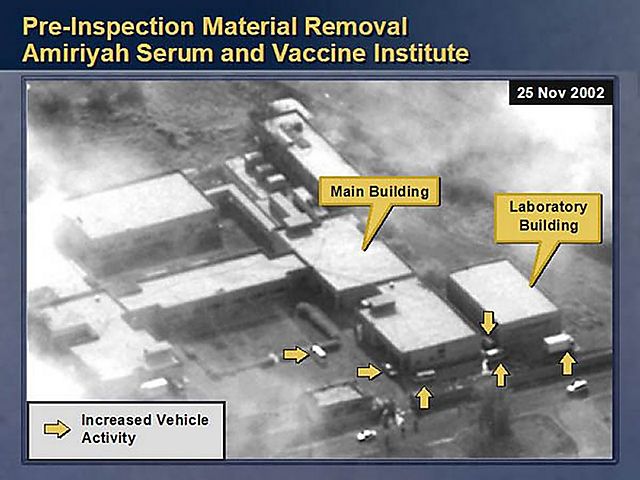

Serum and Vaccine Institute in Al-A'amiriya, Iraq, as imaged by a US reconnaissance satellite in November 2002.

Intelligence assessment, or simply intel, is the development of behavior forecasts or recommended courses of action to the leadership of an organisation, based on wide ranges of available overt and covert information (intelligence). Assessments develop in response to leadership declaration requirements to inform decision-making. Assessment may be executed on behalf of a state, military or commercial organisation with ranges of information sources available to each.

The intelligence cycle

Target-centric intelligence cycle