La Princesse de Clèves is a French novel which was published anonymously in March 1678. It was regarded by many as the beginning of the modern tradition of the psychological novel and a classic work. Its author is generally held to be Madame de La Fayette.

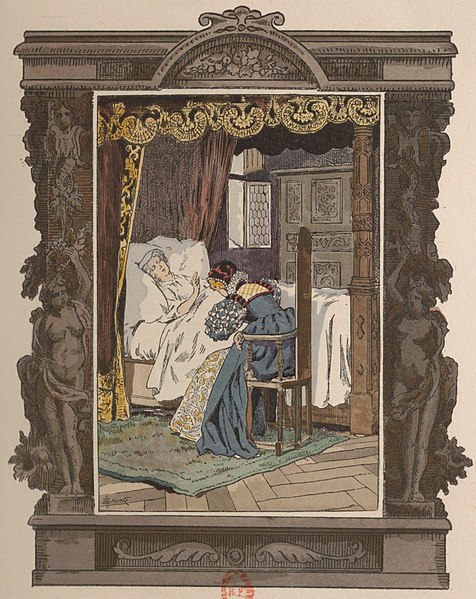

An Image of La Princesse de Clèves

Prince de Clèves sees Mademoiselle de Chartres at the jeweler's shop (Part I)

Madame de Chartres warns the Princess de Clèves against a romantic attachment to the Duke de Nemours (Part I)

The Duke de Nemours speaks privately to the Princess de Clèves (Part II)

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The English word to describe such a work derives from the Italian: novella for "new", "news", or "short story ", itself from the Latin: novella, a singular noun use of the neuter plural of novellus, diminutive of novus, meaning "new". According to Margaret Doody, the novel has "a continuous and comprehensive history of about two thousand years", with its origins in the Ancient Greek and Roman novel, Medieval Chivalric romance, and in the tradition of the Italian Renaissance novella. The ancient romance form was revived by Romanticism, in the historical romances of Walter Scott and the Gothic novel.

Some novelists, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Ann Radcliffe, and John Cowper Powys, preferred the term "romance". M. H. Abrams and Walter Scott have argued that a novel is a fiction narrative that displays a realistic depiction of the state of a society, while the romance encompasses any fictitious narrative that emphasizes marvellous or uncommon incidents. Works of fiction that include marvellous or uncommon incidents are also novels, including Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, and Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird. Such "romances" should not be confused with the genre fiction romance novel, which focuses on romantic love.

Madame de Pompadour spending her afternoon with a book (François Boucher, 1756)

Paper as the essential carrier: Murasaki Shikibu writing her The Tale of Genji in the early 11th century, 17th-century depiction

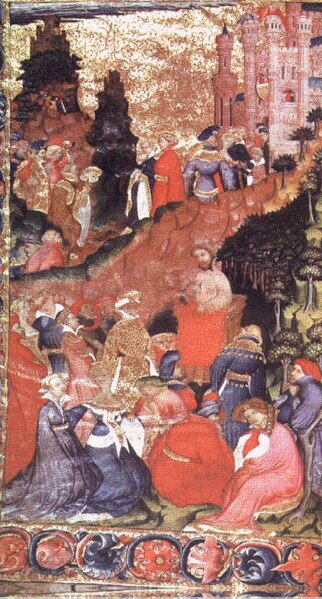

Chaucer reciting Troilus and Criseyde: early-15th-century manuscript of the work at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

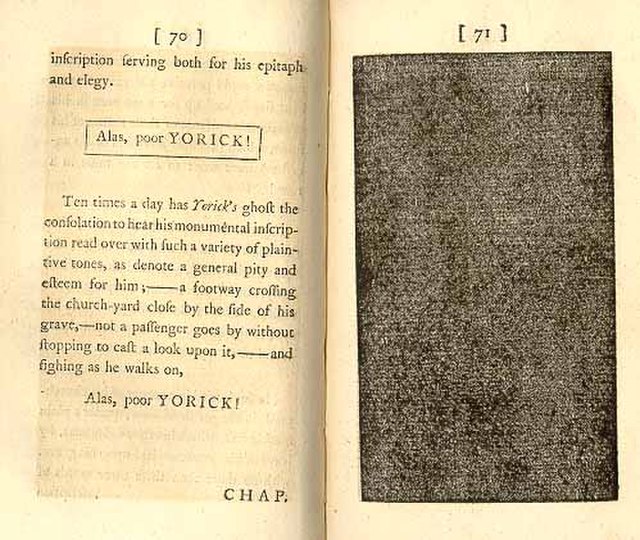

Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy, vol.6, pp. 70–71 (1769)