Maya codices are folding books written by the pre-Columbian Maya civilization in Maya hieroglyphic script on Mesoamerican bark paper. The folding books are the products of professional scribes working under the patronage of deities such as the Tonsured Maize God and the Howler Monkey Gods. The codices have been named for the cities where they eventually settled. The Dresden codex is generally considered the most important of the few that survive.

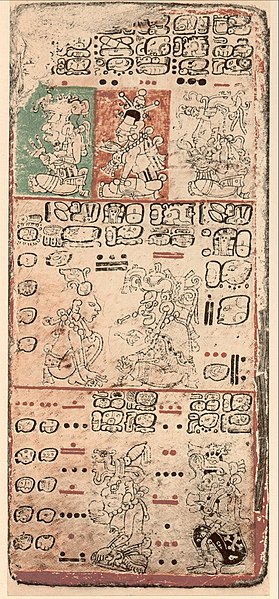

Page 9 of the Dresden Codex (from the 1880 Förstemann edition)

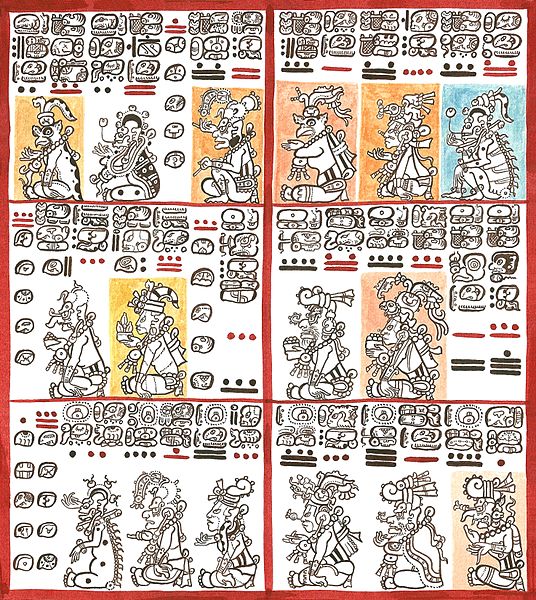

Plates 10 and 11 of the Dresden Maya Codex. Drawing by Lacambalam, 2001

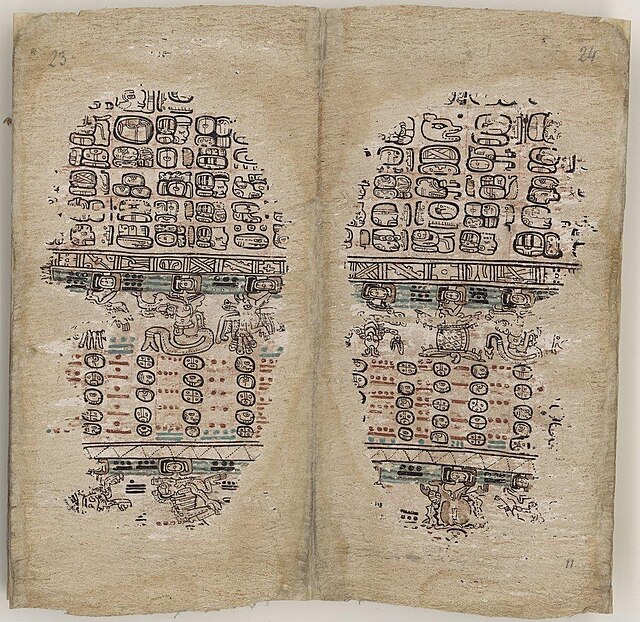

Facsimile of the Madrid Codex, Museum of the Americas, Madrid, Spain

Paris Codex

The codex was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term codex is often used for ancient manuscript books, with handwritten contents. A codex, much like the modern book, is bound by stacking the pages and securing one set of edges by a variety of methods over the centuries, yet in a form analogous to modern bookbinding. Modern books are divided into paperback and those bound with stiff boards, called hardbacks. Elaborate historical bindings are called treasure bindings. At least in the Western world, the main alternative to the paged codex format for a long document was the continuous scroll, which was the dominant form of document in the ancient world. Some codices are continuously folded like a concertina, in particular the Maya codices and Aztec codices, which are actually long sheets of paper or animal skin folded into pages. In Japan, concertina-style codices called orihon developed during the Heian period (794–1185) were made of paper.

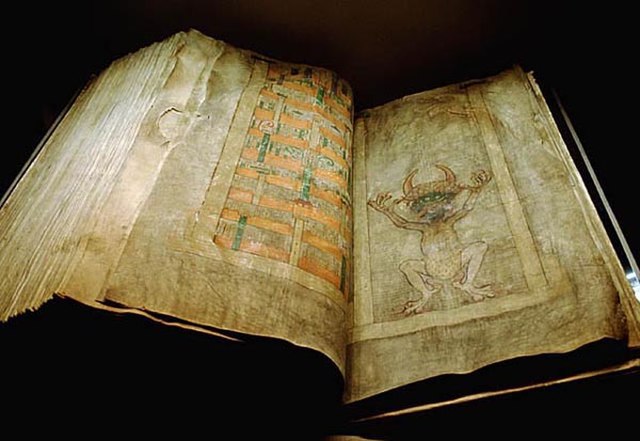

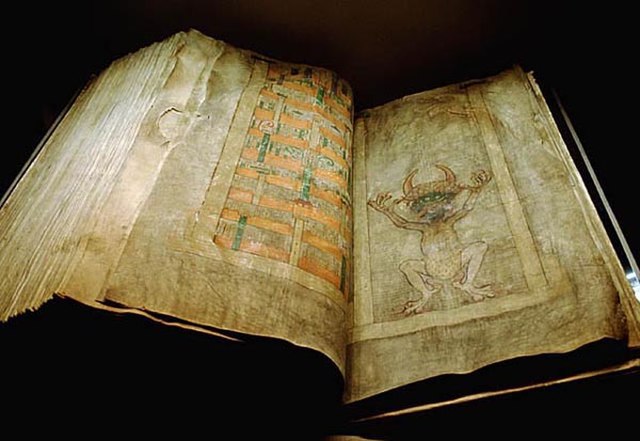

The Codex Gigas, 13th century, Bohemia

The scroll was the document form which was replaced by the codex during the late Roman Empire.

Reproduction Roman-style wax tablet, from which the codex evolved

The Book of Kells is an example of a codex that was created during the Middle Ages.