In medieval music, the rhythmic modes were set patterns of long and short durations. The value of each note is not determined by the form of the written note, but rather by its position within a group of notes written as a single figure called a ligature, and by the position of the ligature relative to other ligatures. Modal notation was developed by the composers of the Notre Dame school from 1170 to 1250, replacing the even and unmeasured rhythm of early polyphony and plainchant with patterns based on the metric feet of classical poetry, and was the first step towards the development of modern mensural notation. The rhythmic modes of Notre Dame Polyphony were the first coherent system of rhythmic notation developed in Western music since antiquity.

Pérotin, "Alleluia nativitas", in the third rhythmic mode.

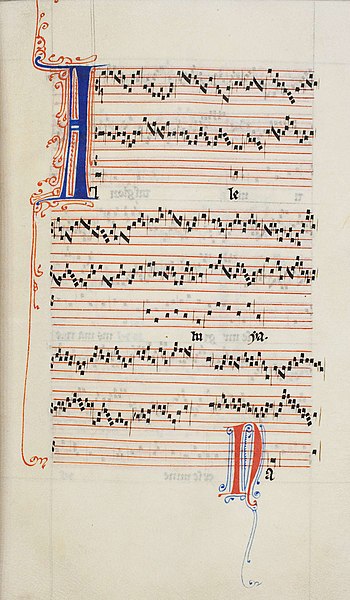

Pérotin, Viderunt omnes (Gradual for Christmas Day), in the first rhythmic mode. MS Florence, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Pluteo 29.1, fol. 1 recto.

Medieval music encompasses the sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the first and longest major era of Western classical music and is followed by the Renaissance music; the two eras comprise what musicologists generally term as early music, preceding the common practice period. Following the traditional division of the Middle Ages, medieval music can be divided into Early (500–1000), High (1000–1300), and Late (1300–1400) medieval music.

A creature plays the vielle in the margins of the Hours of Charles the Noble, a book which contains 180 depictions of medieval instruments, probably more than any other book of hours.

David playing the harp, accompanied by plucked fiddle and clappers/cymbals. Circa 795, Germany or France.

Pérotin, "Alleluia nativitas", in the third rhythmic mode.

Pérotin's Viderunt omnes, c. 13th century.