The simulation heuristic is a psychological heuristic, or simplified mental strategy, according to which people determine the likelihood of an event based on how easy it is to picture the event mentally. Partially as a result, people experience more regret over outcomes that are easier to imagine, such as "near misses". The simulation heuristic was first theorized by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky as a specialized adaptation of the availability heuristic to explain counterfactual thinking and regret. However, it is not the same as the availability heuristic. Specifically the simulation heuristic is defined as "how perceivers tend to substitute normal antecedent events for exceptional ones in psychologically 'undoing' this specific outcome."

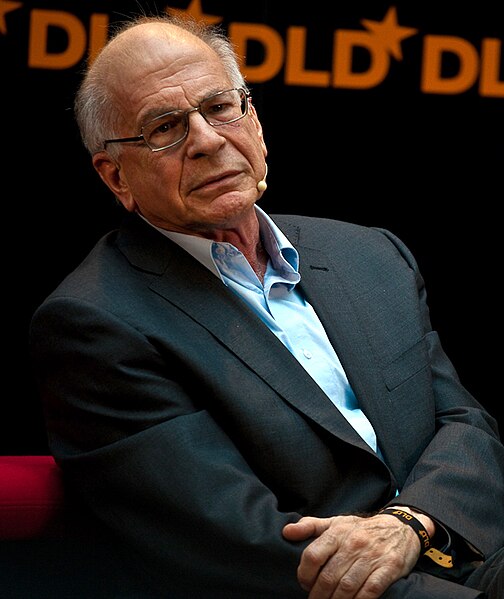

Daniel Kahneman

Heuristics is the process by which humans use mental shortcuts to arrive at decisions. Heuristics are simple strategies that humans, animals, organizations, and even machines use to quickly form judgments, make decisions, and find solutions to complex problems. Often this involves focusing on the most relevant aspects of a problem or situation to formulate a solution. While heuristic processes are used to find the answers and solutions that are most likely to work or be correct, they are not always right or the most accurate. Judgments and decisions based on heuristics are simply good enough to satisfy a pressing need in situations of uncertainty, where information is incomplete. In that sense they can differ from answers given by logic and probability.

Figure 1: Screening for HIV in the general public follows the logic of a fast-and-frugal tree. If the first enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) is negative, the diagnosis is "no HIV." If not, a second ELISA is performed; if it is negative, the diagnosis is "no HIV." Otherwise, a Western blot test is performed, which determines the final classification.

The amount of money people will pay in an auction for a bottle of wine can be influenced by considering an arbitrary two-digit number.

A visual example of attribute substitution. This illusion works because the 2D size of parts of the scene is judged on the basis of 3D (perspective) size, which is rapidly calculated by the visual system.