The Stages of Life is an allegorical oil painting of 1835 by the German Romantic landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich. Completed just five years before his death, this picture, like many of his works, forms a meditation both on his own mortality and on the transience of life.

The Stages of Life

Detail of center section, showing children with the Swedish flag

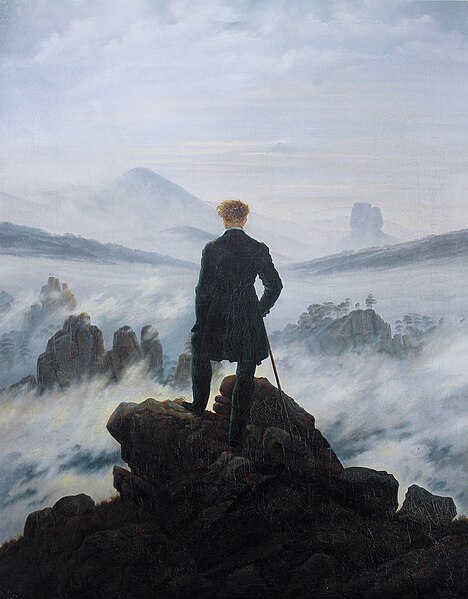

Caspar David Friedrich was a German Romantic landscape painter, generally considered the most important German artist of his generation. He is best known for his allegorical landscapes, which typically feature contemplative figures silhouetted against night skies, morning mists, barren trees or Gothic ruins. His primary interest was the contemplation of nature, and his often symbolic and anti-classical work seeks to convey a subjective, emotional response to the natural world. Friedrich's paintings characteristically set a human presence in diminished perspective amid expansive landscapes, reducing the figures to a scale that, according to the art historian Christopher John Murray, directs "the viewer's gaze towards their metaphysical dimension".

Gerhard von Kügelgen's portrait of Friedrich, c. 1808, Hamburger Kunsthalle

Caspar David Friedrich, by Christian Gottlieb Kuhn (1807), Albertinum, Dresden

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), Kunsthalle Hamburg

Landscape with Pavilion (1797). This early work shows typical themes: ragged landscape, closed gate, building of uncertain purpose.