Zooarchaeology merges the disciplines of zoology and archaeology, focusing on the analysis of animal remains within archaeological sites. This field, managed by specialists known as zooarchaeologists or faunal analysts, examines remnants such as bones, shells, hair, chitin, scales, hides, and proteins, such as DNA, to derive insights into historical human-animal interactions and environmental conditions. While bones and shells tend to be relatively more preserved in archaeological contexts, the survival of faunal remains is generally infrequent. The degradation or fragmentation of faunal remains presents challenges in the accurate analysis and interpretation of data.

Illustration of an Egyptian mummy of a dog

A reference collection of shinbones (Tibia) of different animal species helps determining old bones. Dutch Heritage Agency.

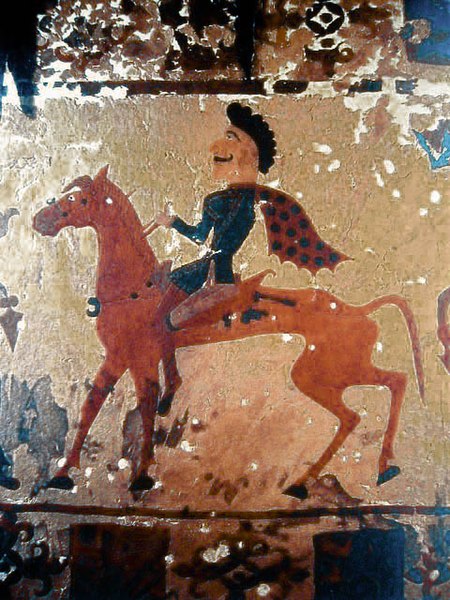

Carpet exemplifying the image of a Pazyryk horseman in 300 B.C. The Pazyryk were known as superb horseman please see Pazyryk culture, other findings alongside the horses can be explored in Pazyryk burials.

Poster of the Zooarchaeology forum in Zagreb (2023).

Domestication is a multi-generational mutualistic relationship in which an animal species, such as humans or leafcutter ants, takes over control and care of another species, such as sheep or fungi, so as to obtain from them a steady supply of resources, such as meat, milk, or labor. The process is gradual and geographically diffuse, based on trial and error.

Dogs and sheep were among the first animals to be domesticated, at least 15,000 and 11,000 years ago respectively.

Rice was domesticated in China, some 13,500 to 8,200 years ago.

Domesticated animals tend to be smaller and less aggressive than their wild counterparts; many have other domestication syndrome traits like shorter muzzles. Skulls of grey wolf (left), chihuahua dog (right)

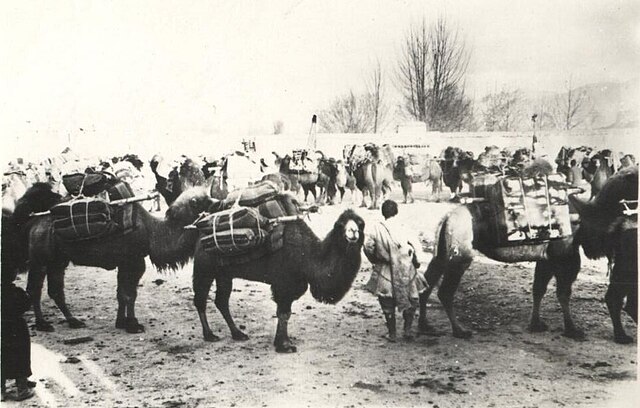

While dogs were commensals, and sheep were kept for food, camels, like horses and donkeys, were domesticated as working animals.